Learning about and from video games

The 2017/18 winter semester at the Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt will see the start of the inaugural Master’s degree in “Games Studies and Engineering”, an interdisciplinary degree covering the culture, practical application and technical development of gaming. Humanities lecturer René Reinhold Schallegger – along with Mathias Lux one of the main proponents – has been working on his habilitation thesis looking at the ethical questions involved in video gaming, and ad astra wanted to know more.

Video games are among the most popular entertainment media worldwide. Yet the quality of their content can often leave a lot to be desired. Are there too few games with aspiration, as with films or in literature?

The problem is that video games are classified exclusively as an entertainment media and are not viewed as art, as is the case with other forms of media. And for this reason, the industry currently prefers to focus on games that generate profit. Games with higher aspirations and socio-critical games are almost exclusively confined to niche indie games. Video games should, however, touch on critical topics, even in the mainstream. Video games can even help us to see life from new perspectives. There is a growing community of gamers who want these kinds of games, and who are also producing them.

Could you give us an example please?

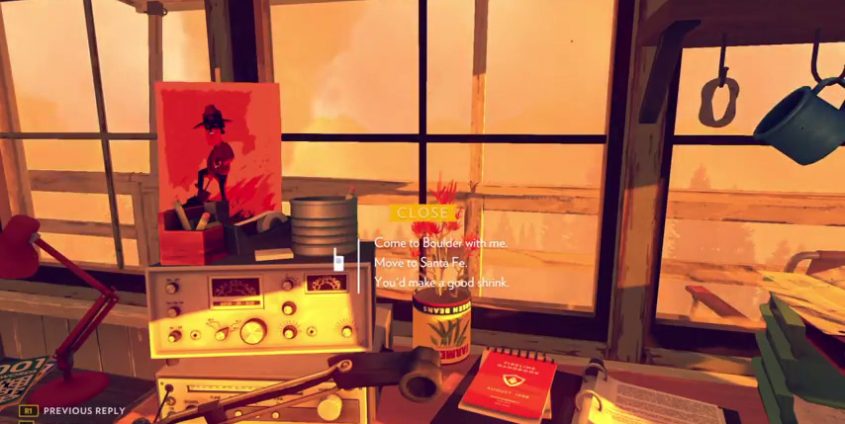

One example is Firewatch from the American studio Campo Santo. The protagonist in this adventure is Henry, a man in his late 30s working as a fire warden in a national park. His wife is somewhat older and is a university lecturer. She is suffering from a rare form of early dementia. And then there’s Delilah, Henry’s superior, who he only communicates with via radio about any particular incidents within the park. The game is played from Henry’s perspective, and the player navigates through the national park with a compass and map.

What makes Firewatch different from the usual games?

It shows that the world isn’t just black and white, and that some problems can’t be solved satisfactorily, or even at all. The protagonist tries to act responsibly, but he doesn’t always succeed. For example, he has to decide whether or not to put his wife in a care home. Regardless of what he does, there is no ideal solution. That’s what is subversive about this game, and also what makes it true to life. Firewatch is more than just an adventure; it’s almost a simulation of real life.

What role do the game’s graphics play?

Firewatch is partly abstracted, or in other words, is not designed to be photorealistic, as is the current trend. The surroundings are highly aesthetic, ‘sublime’ in the Kantian sense. Henry’s psyche and those of other characters’ can even be found reflected in the landscape. The game also tells the story of another fire warden who has disappeared, and his son, as well as the unhappy love affair between two other colleagues.

What can you gain from playing video games?

Video games make it possible for us to develop our systemic and political understanding. My central thesis is that video games are better suited to this than any other medium. They offer us a space to experience and practice what it means to be part of a system, a society in which connections exist with others. And, because they are dynamic, we are able to respond to this dynamism, as well as to the input from other sides. This freedom, which exists because of and in spite of the structure, is what makes playing so exciting. You are part of the system but are simultaneously also inherently subversive, due to the necessity of the configuration. Mechanisms, narrative structures and aesthetics work together to create an interactive experience. The configuration is what makes video games unique, as it allows for more complex concepts to be realised. In linear media, such as literature, interpretation is only possible on one cognitive level.

And who is making it all happen?

The Canadian firm BioWare are taking a leading role when it comes to gender and in terms of diversity. They are pro-actively including transgender and other LGBTQ characters into their mainstream games, just as they would any other character. A lot of the content is optional and the player has to make decisions and then translate them into action. The player is responsible for everything that happens in the game. That in itself is the political aspect of video gaming.

Specially-made educational video games are being used in schools. Do you think this is helping things in the right direction?

I am less of a proponent of serious or educational games being used in school lessons. When games become too didactic they actually cease to be games. What you have then is more of a training program and the aspect of play is removed. That’s why I recommend using standard games. Their preparation is key here: Shakespeare didn’t write his plays as didactic

texts either.

You’ve founded the Critical Gaming Lab together with Mathias Lux. What happens there?

Interested students meet once a month to play together. Afterwards, each of the students writes a short critical spotlight on a different aspect. The analyses are collected together and can then be read online. The aim is to set up an information centre, where academically sound games criteria are used as a tool to help parents, or anyone who wants to buy a game for themselves or someone else.

Registration for the Masters in Games Studies & Engineering opens on 1 May 2017.

Information: www.aau.at/en/master-gse

for ad astra: Barbara Maier

About the person

René R. Schallegger studied English and American Studies at the Alpen-Adria-Universität and gained his PhD there in 2014 sub auspiciis with a dissertation on role plays and post-modernism.

His habilitation thesis has the working title: “Choices and Consequences: Virtual Ethics and the Potential for Cyber-Citizenship in video games”.