Art as midwife for a new Europe

The idea of Europe has run its course. But how can a viable new European idea be established? Klaus Schönberger believes it should be pluralistic and brought about by the means of art. The cultural scientist based in Klagenfurt is leading the three-year Horizon2020 project TRACES, collaborating with eleven partners in ten European countries. ad astra invited him to an interview.

Europe’s common identity is willingly invoked and its cultural heritage is depicted as one entity. Yet, the cultural heritage of Europe also includes many terrible events such as civil wars and genocide. In the course of migration flows, old conflicts are reignited and the fault lines running through Europe are shimmering through. A new definition of Europe is needed. What could this definition be, Mr. Schönberger?

The central idea is to arrive at a conception of Europe that does not strive to arise within the prison of identity, but rather one that identifies the multiplicity, the multi-perspectivity, the transversality, in other words, precisely the diversity as the very core of the European Project. The fact that we are all different should not be understood as a problem, but as a constitutive moment. In this imagination there is space for Muslims, just as there is for Sinti and Roma. What counts is the territorial togetherness of all those, who move around the continent. At that point, we are no longer speaking in terms of an identity, but of a European imagination, in which conflicts co-found that which is European.

What part do old and new conflicts play in this?

In Europe, there are numerous conflicts with political relevance in many places and at different levels. TRACES tracks difficult conflicts and how they are handled, i.e. fraught and traumatising elements within cultural heritage, which are exploited, again and again, for political purposes. Clearly, this exploitation often serves to continue social divisions. We do not deny these conflicts, but we do see in them the potential of that which is held in common. It may sound paradoxical, but it is incredibly productive.

How can conflicts contribute?

Conflicts are normal, and they represent the starting point of our notion of a European idea. The conception of a homogeneous identity negates the conflict and the opposing interests. By contrast, we maintain that all these disputes should also be part of the European idea. We are searching for and developing methods that will allow us to render these conflicts positive for something akin to a new European imagination.

How can they shed their divisive force?

By taking the instances of resistance and the contradictions seriously and no longer comprehending them as antithesis. Thus, the emerging renationalisation is an expression of conflict escalation, of diverse interests and antagonisms on various levels. This needs to be endured and converted into something positive. It is necessary to shift from an antagonistic to an agonistic perspective. This understanding of a European democracy sees contradictions and conflicts as normal and develops processes of negotiation. The important thing is that the contradictions and conflicts are allowed to remain, but that the positions of the opponents are recognized as valid.

An arduous process. Are there any successful examples?

It is possible to regard the Carinthian consensus talks about a bilingual Carinthia as just such an agonistic process. The contradictions have remained, but they are fenced in by a political process, which is beginning to replace the friend-foe mode of thought. The key point is that by following this route, the disparate interests do not become irrelevant. Instead, the aim is to dissolve the friend-foe relationships into a kind of antagonism, which recognizes the different interests and renders them visible.

TRACES is one of the first large joint EU projects to be managed culture-anthropologically with art as an equal partner. What convinced the reviewers?

It seems likely that we were selected because we represent a new methodological approach and particularly, because we are proceeding experimentally. In five projects, the so-called Creative Co-Productions (CCPs), we are focusing on a comprehensive and long-term joint collaboration between science, art, and mediating institutions. To date, what has tended to happen is that artists visited a museum, created an intervention, and that was it. We, however, are testing a different approach. It requires the scientists, artists, and the institutions to engage with each other. The opportunity to work together for a period of three years is usually not very easy to realise in the context of art.

Aren’t you exploiting the art and its actors by doing this?

It’s a bit more complicated than that. Yes, up until now cultural heritage institutions have exploited artists much as companies do so with consultants. If the bosses can’t bring themselves to make a decision, they hire management consultants, whose job it then is to attribute economic rationality to the course of actions. In cases where it is no longer clear what exactly constitutes the cultural heritage, then the use of art serves to draw a veil over the perplexity. But the reverse is also true. In our project, artists are doing something that fundamentally challenges the traditional notion of art and transcends the framework of the art market.

And yet art rarely delivers unequivocal answers!

That’s as it should be. In the case of art, it is always a balancing act. There are two options: Art can allow alternative approaches and produce another openness towards complex contradictory interests. But, in a difficult sense, it can also become imprecise. That is our central research question: How and in which circumstances can art contribute to another form of mediation – in the agonistic sense – of difficult cultural heritage?

The EU is expecting concrete directions for a broader application. What’s the plan?

Within the scope of the project, we will develop a tool for the practical application in the context of art. It is of primary importance that the ambiguity of art and the processing of the conflicts by way of artistic interventions and approaches such as vagueness, nebulosity, and heterogeneity are not seen as a problem, but as a productive factor. Associated alternative approaches could help to dissolve battle lines and render them ambiguous. The open form, imminent to art, also delivers numerous possible interpretations. With these, rigid patterns of interpretation can be dismantled, but the opportunity can also arise to become precise about imprecision. Imprecision harbours the chance of an opening communication about problematic topics.

Barbara Maier for ad astra

Klaus Schönberger

Born in 1959, he was appointed Professor of Cultural Anthropology at the Department of Cultural Analysis at the AAU in 2015. He studied in Tübingen, completed his post-doctoral studies in Hamburg and most recently taught at Zurich University of the Arts.

About the project

The project “TRACES. Transmitting Contentious Cultural Heritages with the Arts – From Intervention to Co-Production” is funded by the European Horizon2020 Programme to the tune of 2.3 million euro and by a Swiss contribution totalling 400,000 franc. It is managed and coordinated by Klaus Schönberger and involves universities, artists, cultural institutions and memorial sites from Northern Ireland, Italy, Germany, Norway, Switzerland, Romania, Scotland, Poland, Slovenia and Austria.

The five creative co-productions (CCPs):

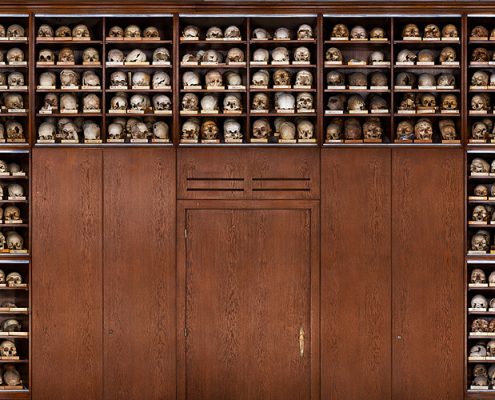

- Dead Images (Vienna – Edinburgh, GB) is dedicated to conveying the collection of skulls and the anthropological collection of photographs kept at the Natural History Museum in Vienna.

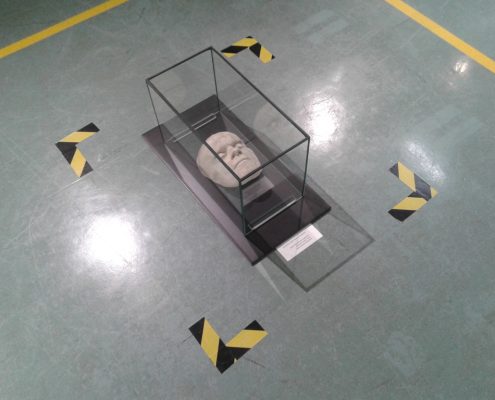

- Casting of Death (Ljubljana, Slovenia) studies the exploitation of historical death masks of prominent people as instrument of political propaganda.

- Absence of Heritage (Medias, Romania) is an attempt to re-implement the missing memory of the Jewish community destroyed during the Ceaușescu era.

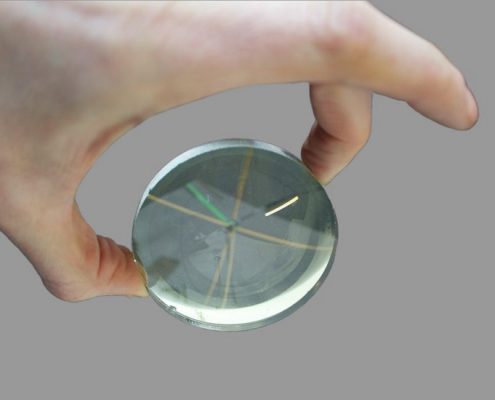

- Awkward Objects Of Genocide (Krakow, Poland) deals with artistic artefacts made by witnesses to the Holocaust and their forms of presentation.

- Transforming Long Kesh (Belfast, Northern Ireland) is a collaborative social sculpture by artists Martin Krenn and Aisling O’Beirn exploring the future of the former prison Maze/Long Kesh.

In addition to these five methodological tools, the CPPs, there is a wide range of ethnographic, descriptive and mediating projects in London, Florence, Frankfurt/ M. and in the Alps-Adriatic Region, with the University Cultural Centre UNIKUM amongst others.